“For me, Namibia represents not only ties of family and friendship but also the effort to the balance between humans and the environment so crucial to our future.”

She asked about my family and my country. When I offered to help in any way I could, she said she couldn’t ask for more than a visit and a conversation. She was generous and dignified, and her eyes had such clarity. Sometimes when I have a hard day, I see her smile, and the way she held her body, as if she would give all her remaining strength to her baby. Two weeks after we met, it was 9/11. With all that has happened since in Afghanistan, I can’t imagine how she could have made it. Did her husband make it back before they demolished the camp? Did she give birth there, or was she forced out? Is she sitting in a tent on a border somewhere with her child, who’s now a teenager?

I read recently that the World Economic Forum predicted that it will take 83 years for the gaps in rights and opportunities between women and men to close in all countries. This is not about progress for women at the expense of men, but about finding an equal balance that benefits everyone. Eighty-three years seems far longer than anyone, man or woman, would ever hope for or imagine.

My mother, who was part Iroquois Indian on her father’s side, taught me the Iroquois saying that we should consider the impact of our decisions upon the next seven generations. It is hard for us to be that thoughtful, with all the pressures in our lives, but it seems to me to be a beautiful aspiration.

So whoever you are as you read this—a doctor, lawyer, scientist, human rights activist, student, teacher, mother, wife, or boy or girl flipping through your mother’s copy—I hope that you will join me in taking time today to think about how we can all contribute to making a better future.

There is a lot we can’t predict about the world 150 years from now. But we do know that our great-grandchildren will be living with the consequences of decisions we make now, just as we can trace the origin of problems we are dealing with today to their roots in earlier centuries.

It was early in the 19th century, for example, that the craze for ivory and other products made from wild animals took off in some countries, along with wider destruction of the environment. Where millions of elephants, lions, and other species once roamed the African continent, today small, scattered populations cling on in the face of relentless poaching and the expansion of agricultural land reducing their natural habitat.

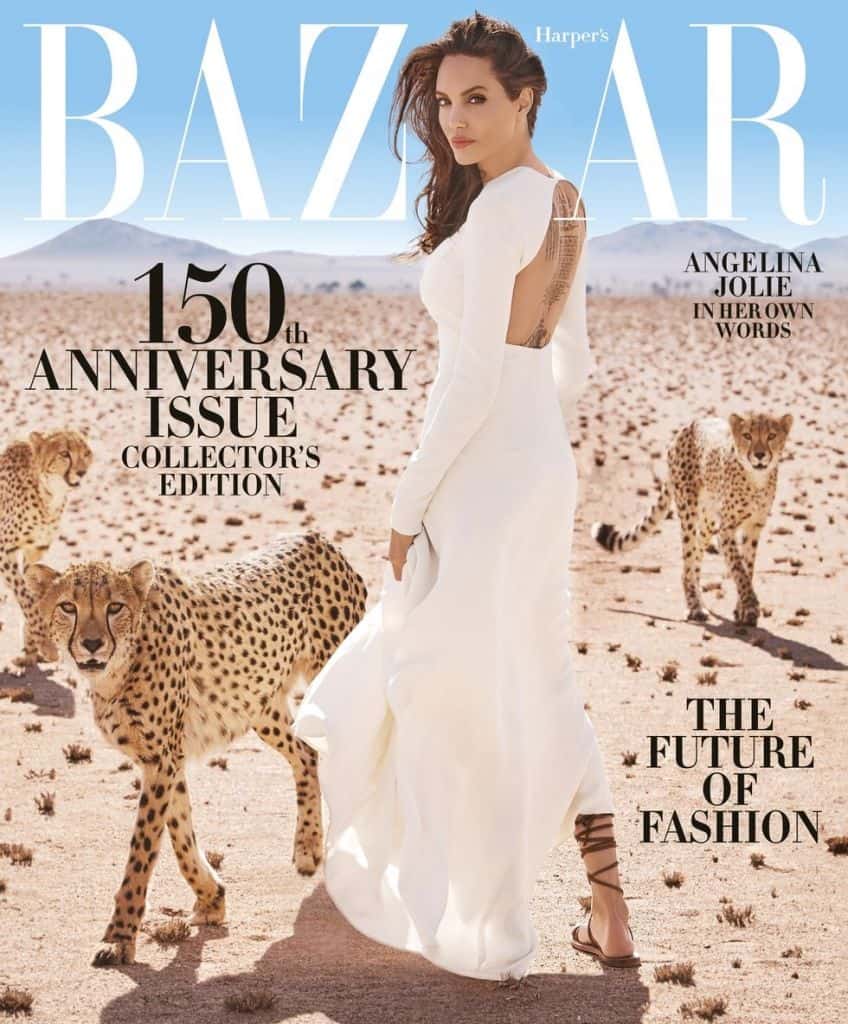

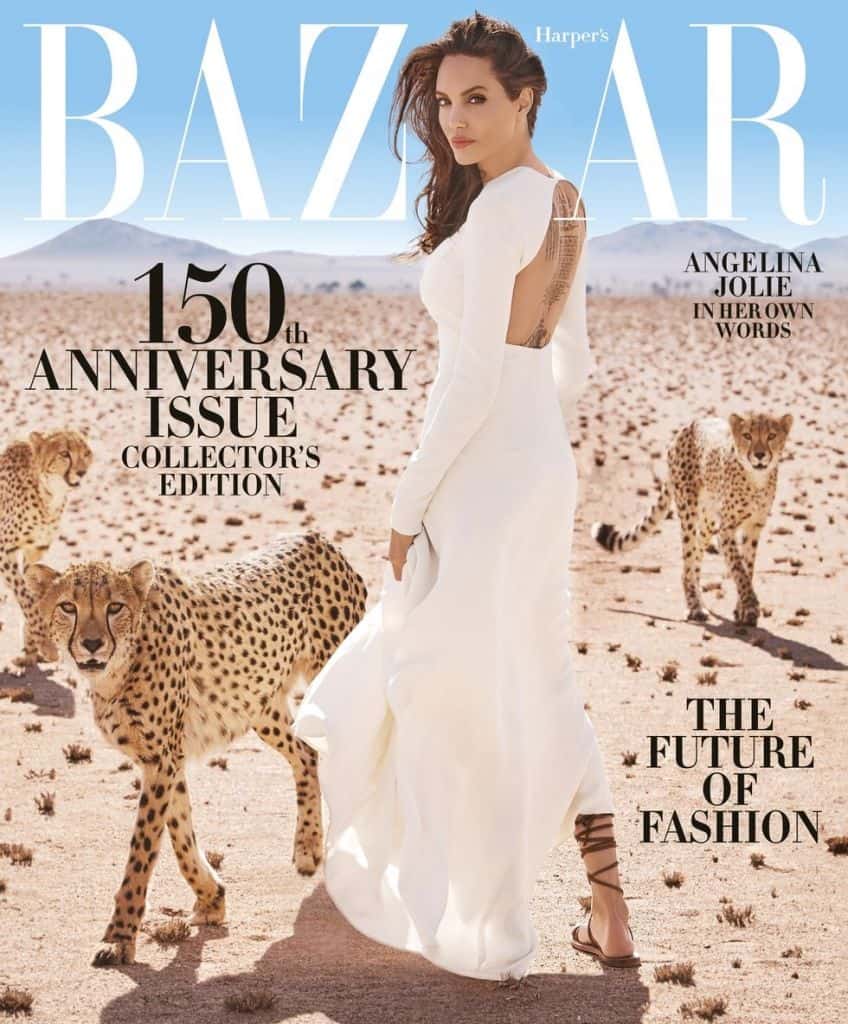

The photos alongside this piece were shot at a nature reserve in Namibia’s Namib desert. The reserve is run by the N/a’an ku sê Foundation, led by my friends Marlice and Rudie van Vuuren. Our daughter Shiloh was born in Namibia, and our family has worked with Rudie and Marlice on conservation in that country over the past decade. For me, Namibia represents not only ties of family and friendship but also the effort to find the balance between humans and the environment so crucial to our future.

The N/a’an ku sê Foundation works with Namibia’s San people, who are considered to be the world’s oldest culture. They represent thousands of years of man and wildlife coexisting in harmony, but they have suffered, like other indigenous peoples, from being forced off their lands by farming, unchecked development, and the depletion of wildlife. The destruction of natural habitat and wildlife has left the San people unable to hunt and support their families.

“If my life experience has taught me anything, it is only what you stand for, and what you choose to stand against, that defines you. As the San people say: you are never lost if you can see your path to the horizon.”

The same thing is happening all across the globe—in Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific—and women are often the most affected. Women make up most of the world’s poor. It often falls on them to find food, water, and fuel to cook for their families. When the environment is damaged—for example, when fishing stocks are destroyed, wildlife is killed by poachers, or tropical forests are bulldozed—it deepens their poverty. Women’s education and health are the first things to suffer. The environment is also a crucial factor in future global stability, with 21.5 million people displaced worldwide by climate change every year, as part of the more than 65 million people displaced in total.

N/a’an ku sê works to preserve the natural habitat and to protect endangered species, such as elephants, rhinos, and cheetahs, like the ones pictured in this story. I first encountered them in 2015, when they were small cubs and our family sponsored them. They’d been orphaned, and nearly died. They were nursed back to health, but they cannot be returned to the wild, as they have lost their fear of humans and could be killed if they stray onto farmland. With cheetah numbers plummeting to fewer than 7,100 worldwide, the mission is to save every animal possible.

These cheetahs are not pets, nor should any wild animal ever be kept as one. They inspire us to help preserve these unique, majestic creatures in the wild, as just one of many steps to preserve the environment for future generations.

Each of us has the power to make an impact through our everyday choices. For instance, we can commit to never buying illegal wildlife products such as ivory or rhino horn.

Fashion was once a major factor in encouraging the demand for clothes, jewelry, and objects made from wildlife parts. But magazines can now send a different message: that wild animals belong in the wild, and that ivory is not beautiful unless on the tusk of a living animal.

What we do, each in our own small way, matters. The hopeful thought is that it is in our hands. Over the next 150 years, technology is going to give us more and better means of communicating, fighting poverty, defending human rights, and caring for the environment. But it is what we choose to do with the freedom we have that will make all the difference. If my life experience has taught me anything, it is that what you stand for, and what you choose to stand against, is what defines you. As the San people say, “You are never lost if you can see your path to the horizon.”